![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() As founder and naming member of the legendary group The Platters, Herb Reed racked up an impressive list of achievements. He and his group performed sold-out shows in more than 100 countries; made nearly 400 recordings and sold millions of albums, earning the group membership in the Rock and Roll, Vocal Group and Grammy Halls of Fame.

As founder and naming member of the legendary group The Platters, Herb Reed racked up an impressive list of achievements. He and his group performed sold-out shows in more than 100 countries; made nearly 400 recordings and sold millions of albums, earning the group membership in the Rock and Roll, Vocal Group and Grammy Halls of Fame.

Reed, 83, who sang bass for The Platters on such hits as “The Great Pretender,” “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” “Only You” and “Twilight Time,” died on Monday, June 4, 2012, after a period of declining health.

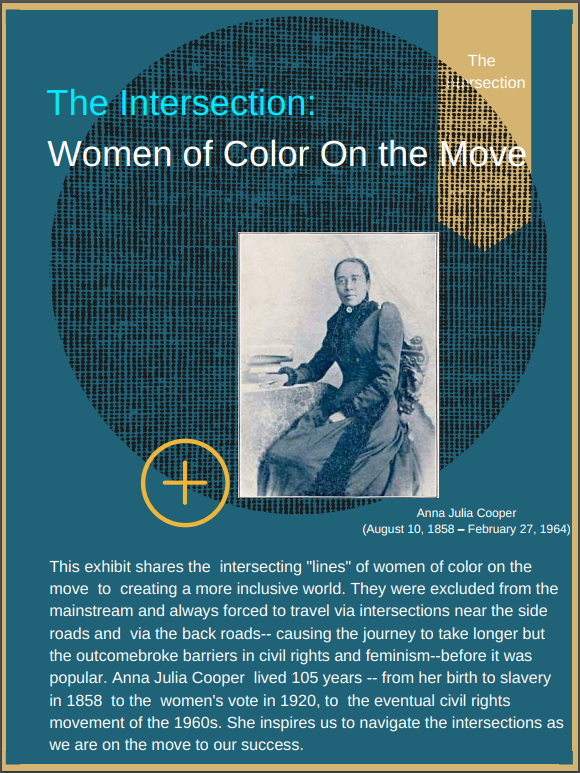

Despite enviable recording industry acclaim, it was a recent accomplishment that Reed considered among the most important of his life. In 2011 a federal court judge in Nevada ruled that Reed possessed superior rights to the name The Platters, a decision that returned to Reed rights to the name of the group that he founded with three other men in 1953 making him the sole heir to the group’s tremendous legacy.

“You know a lot of people tell me to just hang it up,” Reed told his biographer in early 2012, “but I just cannot do that. It’s not right to have someone steal your name. It’s just not right. We were cheated back then, but that’s how things were done then. It’s doubly wrong to face it again today. It’s theft, and I have to fight so that no other artist faces this.”

When Reed learned of the court’s decision he was elated. “He teared up and told me this was the most important thing he had done. He joked that he was going to have the judge’s decision framed and hung up along the gold and platinum records that line the walls of his home,” said Frederick J. Balboni Jr., Reed’s and his company’s manager.

It was a long journey to success for the elder statesman of the recording industry. Reed was born into abject poverty in segregated Kansas City, Mo., in 1927. “I was poor, and I’m not ashamed to share those stories now, particularly with young people,” recounted Reed in a recent interview. “I was so hungry I couldn’t think. I would skip school because I was so hungry.”

Reed, whose parents never had a steady home and died when he was barely a teen, spent his childhood bouncing from the homes of extended family members until at age 15 a friend offered to have Reed ride along with her to Los Angeles (a city he had never heard of before). He had just three dollars in his pocket and a cigar box containing a toothbrush, comb and handkerchief. He didn’t even own a change of clothes.

In Los Angeles, Reed quickly met people and made new friends, some of whom gave him a place to stay and helped him land a job at a car wash that paid $20 a week. In his newfound hometown, Reed sang with friends—something he had done back in Kansas City—but never thought of it as a career. “Those days were learning days before the recordings,” Reed told The Boston Globe in a 2006 article. “I learned how nice people could be and learned responsibility. I learned that it is better to be honest than dishonest.”

In 1953, Reed started a group of harmonizing street singers with three other men—Joe Jefferson, Cornell Gunther and Alex Hodge—and it was Reed who picked the name The Platters, inspired by disc jockeys who called records “platters.” None of them played any instruments, but they could sing, mostly popular songs of the day.

With Reed singing lead, they won first place at amateur shows around Los Angeles. Soon after, David Lynch replaced Jefferson, and Tony Williams replaced Gunther and became the group’s lead singer. Between working at the car wash and other odd jobs, the group would spend nights and weekends driving up and down the California coast, performing and making a few dollars, which they would split and use for gas money. In late 1953, they met the business-savvy songwriter Buck Ram, who became their manager and would pen the group’s biggest hits. The following year, Paul Robi replaced Hodge, and they added a female singer, Zola Taylor. The Platters signed a recording contract with Mercury Records in 1955, and the group started accumulating hit singles.

Reed was the last to survive of the five original members from the group’s first recording contract. He continued to tour regularly as long as his health permitted—nearly 200 shows a year—many on cruise ships in the Caribbean with a new generation of The Platters as Herb Reed and The Platters or Herb Reed’s Platters.

Reed was the only member of The Platters to record on all of their nearly 400 recordings, which remained popular throughout the years. He liked to use a few statistics to illustrate the group’s continuing popularity: since the changeover to Compact Disc technology in the mid 1980s, more than CDs featuring The Platters have appeared in the marketplace, with estimates of over 60 percent of them being bootlegs.

Reed, who kept up with the latest technology, worked with his manager Mr. Balboni and Messers Dan Norris and Eric Sommers of their legal team to remedy the many wrongs perpetrated on the group. Recently the team was able to track down new recordings he considered deceitful like a “Best of” compilation of The Platters biggest hits with a photograph of the original group from the 1950s used to promote tracks recorded in the 1990s by an unofficial group that were being sold to an unsuspecting public. “It isn’t just the royalties, far from it,” Balboni said. “Herb told me just a month or so ago that it always bothered him that the fans, who were so loyal and would turn out in droves and follow them all over the world, were being cheated. Herb hated the thought of fans being duped.”

Reed developed a keen sense of the music business, but credits his early life of poverty with giving him the tools he needed to survive in the music business. When The Platters received their first big royalty check, Reed saw that other members of his group went out and splurged on cars and nights on the town. Reed, however, bought a multi-family house in Los Angeles. “I never thought that it would keep going, and I never wanted to assume we’d keep getting checks,” he told an interviewer in 2012.

After many years of living in Los Angeles and Atlanta, Mr. Reed settled in the Boston area “because the people there were always so nice to me. They weren’t just fans,” Reed told the writer working with him on his autobiography. Reed lived in Arlington, Mass., for the last several years and maintained a home in Miami, Fla. Reed, who outlived all of his siblings, leaves a son Herbert, Jr. and three grandsons.