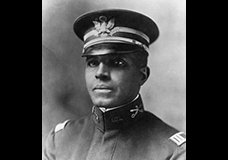

Colonel Charles Young, trailblazer that has exceeded all expectation, deserves recognition as an honorary brigadier general, given his responsibility, track record and committment to service. However, the Center for Military History claims that he does not deserve the honorary title, even though the Colonel’s barrier-breaking leadership was clear and evident. The recent editorial by Arelya J. Michell, Publisher/Edior-in-Chief, The Mid-South Tribute and the Black Information Highway addresses the response shared by the Center for Military History.

Colonel Charles Young, trailblazer that has exceeded all expectation, deserves recognition as an honorary brigadier general, given his responsibility, track record and committment to service. However, the Center for Military History claims that he does not deserve the honorary title, even though the Colonel’s barrier-breaking leadership was clear and evident. The recent editorial by Arelya J. Michell, Publisher/Edior-in-Chief, The Mid-South Tribute and the Black Information Highway addresses the response shared by the Center for Military History.

Center for Military History Answers with Gobbledygook on

Col. Charles Young Honorary Promotion

By Arelya J. Mitchell, Publisher/Editor-in-Chief

The Mid-South Tribune and the Black Information Highway

The U.S. Center for Military History (CMH) responded to our editorial entitled “Col. Charles Young Denied by the Center for Military History”* (July 26, 2013). But we’ll get back to that shortly.

First, the following quote: “Young’s retirement dashed the high expectations of Negroes, and the colonel soon became a symbol of their disillusion. They pointed out that he was one of the few field grade officers with Pershing in Mexico whom the general had recommended to command militia in the federal service.

Okay. Let’s pause here. General John J. Pershing, a legend in U.S. military history, recommended Col. Charles Young to “command militia in the federal service”.

Shall we commence with this quote? Then let us proceed: “Others subsequently supported the claim that Young was retired ‘because the army did not want a black general’ by quoting white officers who had said as much in public addresses. Col. Young, over years, attained the stature of a martyred hero.”

…[R]umors of wholesale arrests of Negro officers and enlisted men made the rounds…During the course of the war, Negroes had expressed two major grievances. One centered on[the] retirement in June 1917 of Col. Charles Young, highest ranking Negro Regular Army officer, on the eve of what many Negroes had expected and hoped would be his appointment to a field command.”

These passages are from a nearly 800 document entitled “The Employment of Negro Troops” by Ulysses Lee, published under the auspices of the venerable U.S. Center for Military History itself and endorsed by Brigadier General Harold W. Nelson in a 1994 republishing, again under the auspices of the venerable U.S. Center for Military History.

Brigadier General Nelson wrote: “Ulysses Lee’s The Employment of Negro Troops has been long and widely recognized as a standard work on its subject…As a key source for understanding the integration of the Army, Dr. Lee’s work eminently deserves a continuing readership.”

This torch of getting the U.S. Army to do the right thing by Col. Young has been passed to the National Coalition of Black Veterans in a 21st Century America. The Coalition asked for a presidential proclamation for a promotion of Col. Young to Honorary Brigadier General. But that apparently is a hard pill for the Center for Military History to swallow.

Past wrongs are like ghosts: They never die.

Now back to the Center’s response to the National Coalition of Black Veterans on our editorial. We asked in the editorial how Col. Young’s records were destroyed. The Center stated that his military records were destroyed in a fire in 1973.

A Center spokesman wrote: “As to CMH denying his appointment to Brigadier General, we simply do not have authority to approve or deny such a request for anyone, living or dead.”

As stated in our previous editorial, the Center was charged with looking into the matter of Col. Young’s honorary promotion when the Coalition contacted Cong. Barbara Lee who then wrote a letter to President Barack Obama. The Coalition involved Cong. Lee because its previous correspondence to the President was taking so long that one would have thought the Pony Express was still in service. These letters* were written by Charles Blatcher III, chairman of the National Coalition of Black Veterans and founder of the National Minority Military Museum Foundation, and by Howard D. Jackson, chairman of the National Minority Military Museum Foundation. Nearly 30 organizations, some Brigadier Generals, other African American high ranking officers, and rank and file soldiers have joined in this cause only to be ignored by the Center.

The Center’s response continues: “CMH was asked to look into his career, which was, as we all know quite notable. His service was truly amazing and his accomplishments legion. However, as was mentioned in the article, we were asked to evaluate service at the general officer level. This was a test we felt he did not meet as he was a colonel.”

Okay, let’s break this down. From the above paragraph, we can ascertain that the Center cannot promote; it just evaluates.

Obviously, the Center evaluated and concluded that Col. Young did not merit an honorary promotion posthumously or any other way.

Now let’s repeat the Center’s reasoning: “This was a test we felt he did not meet as he was a colonel.”

What test? Where is this invisible test? Now hold the horses, as they say, because “This was a test [the Center for Military History] felt he [Young] did not meet as he [Young] was a colonel.”

Now take a moment and recollect that the National Coalition of Black Veterans’ specific request was to get the Colonel promoted posthumously to Honorary Brigadier General. So why would the Center evaluate him on a “test” to meet the criterion to be promoted to what he already was which was a colonel?

Classic Catch 22. Classic gobbledygook.

Now sit down, drink your Kool-Aid and think on the Center’s next point of its response: “Had they [the U.S. Army] taken him [Col. Young] back in for World War I service—and certainly race played as a major issue in that decision—he would have had general officer experience if not rank.”

Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition! Because the Center has shot itself in the foot!

Let’s break down the Center’s reason which goes into some type of dialectical regression towards what can only form a synthesis of official bull crap. From the Center’s reason, one must presuppose that Col. Young would have been promoted if he had gone into World War I, because World War I would have determined his merit to become an Honorary Brigadier General or at any rate to be promoted, period.

To reiterate, World War I would have been the criterion on which rested the legitimacy of promoting Col. Young posthumously. Of course, a General Ulysses Grant would not have been promoted because he did not serve in World War I. Oh, but he was white. Oh! Oh! He was dead when World War I broke out and his record in the Civil War theoretically would not have counted had he been African American. Oh! Oh! Oh! But he was white. And that means one had to be a white officer and NOT have served in World War I to qualify for promotion. Honorary or otherwise. After all, the Center did admit that “certainly race played as a major issue in that decision.” You think!

However, apparently the Center failed to ‘evaluate’ on its invisible ‘test’ how ‘race’ led to Col. Young NOT being promoted; otherwise, the Colonel would have passed with flying stars. Had he NOT been Black.

Bottom line: When Col. Young sought promotion, white officers complained. Initially, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker essentially told these officers to get over it. One officer complained to Mississippi Governor Theodore Bilbo who served the state from 1916-1920 (first term). The white officer was so upset that he might have to answer to a Black man that he went whining to the nation’s staunchest segregationist and a V.I.P. in the Ku Klux Klan, Bilbo who to this date is legendary as a racist and Jim Crow advocate. This officer like legions of other white officers started asking for transfers.

Bilbo was so furious that this white officer might have to subjugate himself to a Black man that he complained to President Woodrow Wilson. And being an astute politician, Wilson didn’t want to get on the bad side of the South. Subsequently, as Commander- in-Chief Wilson squashed Baker’s directive for white soldiers to get over it. This stopped Baker cold from sending Young into World War I. If Young had gone in as a commander of Black troops, he would have been eligible for the Brigadier General rank, and at that point a newly Black Brigadier General would have white officers under his command whether the whites liked it or not. So, Gov. Bilbo, President Wilson, Secretary of War Baker and a host of white officers conspired to block Col. Young by concocting a medical reason to force his retirement. These are FACTS. What invisible test did not include these facts? Were these facts used for the Center’s evaluation? Would these facts not qualify as a “major issue in that decision”?

Did the Center evaluate the fact that Col. Young fought gallantly and patriotically in the 1916 Punitive Expedition between the U.S. and Mexico. This is the war which made Pancho Villa famous. In this conflict, Col. Young was responsible for saving the lives of white Gen. Beltran and the troops of the 13th Cavalry. This space cannot provide other acts of courage and the full career of Col. Young.

Furthermore, why did not the Center investigate these white officers who asked to be transferred? Were their records lost in a fire, as well? We are sure some of them went on to get promoted with their white skin being the foremost criterion.

By the same token, the National Coalition of Black Veterans is asking for an Honorary Brigadier General rank for Col. Young, we are asking for dishonorable demotions of those white officers who played a role in blocking Col. Young’s promotion. Surely, it cannot be that hard for the Center to investigate who these officers were seeing that, as the Center says, “race played as a major issue in the decision.” Surely, an invisible “test” can be concocted on which to “evaluate” these white officers and the conspiracy condoned by the U.S. Army.

The Center’s response to a venerable group such as the National Coalition of Black Veterans was not only disrespectful but a slap in the face to all African American war veterans living and dead. To all African American soldiers period. To all African American citizens.

In our previous editorial, we cited that this is the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington and the commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s death. We also asked that Kennedy’s famous quote be rephrased in Col. Young’s case to: “Ask not what this Black soldier can do for his country, but what this country can do for this Black soldier.”

###

This editorial is on the Editorial, Op Ed, Black Paper, and Black History lanes on The Mid-South Tribune and the Black Information Highway at www.blackinformationhighway.com . Welcome, Travelers!

To help get Col. Charles Young an Honorary Brigadier General promotion, please call The Colonel Charles Young Promotion Campaign at 510-467-9242 or email to CNMMMF@aol.com .

* “Col. Charles Young Denied by the Center for Military History” and Coalition letters are on the Editorial and Letters lanes on The Mid-South Tribune and the Black Information Highway at www.blackinformationhighway.com .

**Coalition partners are: The National Minority Museum Foundation, Oakland, CA; The American Legion-Charles Young Post #398, NY, NY; The Congressional Black Caucus Braintrust, Washington, D.C.; Los Banos Buffalo Soldiers 9th and 10th Cavalry, Los Banos, CA; The USCG National Association of Former Stewards and Mates, Laurelton, NY; The Buffalo Soldiers Memorial Committee-Inland Empire Heritage Association, Riverside, CA; The Association of the 2221 Negro Infantry Volunteers World War II, Ft. Washington, MD; The 9th Memorial United States Cavalry Association, Marana, AZ; The National Association of Black Veterans, Inc., Milwaukee, WI; The African American Patriots Consortium, Inc., Baltimore, MD; The American Legion-Cook-Nelson Post #20, Pontiac, MI; The 9th and 10th Horse Cavalry Association, Los Angeles, CA; The 555th Black Paratroopers Association, Tampa, FL; 369th Veterans Association, Staten Island, NY; The 715 Veterans Association, Laurelton, NY; Montford Point Marine Association, Inc., Limerick, PA; 761st Tank Battalion and Allied Veterans Association, Chicago, IL.; The African American Gallery of the Ethnic Heritage Museum, Rockford, IL; and the Aces Museum, Philadelphia, PA.